Ancient Greece – the era of great philosophers whose tradition is the foundation of our part of the world. During those times, for example, the concept of "free time" was established and it was described as a space for a better understanding of oneself, which laid the foundations of ancient society and its culture. The citizens of Ancient Greece in their free time pursued music or other arts, including physical ones – sports.

Space to explore yourself

However, the art of war was also considered an art form then. The Greeks also practiced intellectual conversation, which took them a lot of time as their way of life wasn't as hasty as it is today.

However, free time only concerned a certain social stratum, while others were forced to pursue hard work (slavery was in place). Although free time was predominantly considered a privilege of men of the upper class, it was also available, to some extent, to women and slaves. Nonetheless, the degree to which the free time was available to them varied greatly depending on the class and gender.

Free time is considered crucial for personal growth, because it provides space for finding answers to important questions about life and human beings. It leads to self-development through striving for harmony of individual components of the personality. In ancient times, this harmony was represented by the concept of kalokagathia (kalos=beautiful, kagathos=good). It was a concept referring to wholeness, the foundation of which is the unity of physical virtues and a noble spirit. Sport and art were thus perceived as two sides of the same coin.

What’s right is beautiful

Unlike today, the word "beauty" in classical Ancient Greece wasn't so easily separable from other positive qualities. The Oracle of Delphi answered the question of measuring beauty: "The right is the beautiful." The Greeks saw the ideal of beauty as the cosmis order (the Ancient Greek word kosmos meant not only "the universe", but also "adornment" or a person wearing makeup, hence the word cosmetics). The sculptors of classical Greece tried to depict this cosmis order by symmetry. That was also the goal of Myron, the author of the legendary Discobolus, to express the psychophysical beauty that brings the soul and body into harmony.

.jpg)

For centuries, the statue of Doryforos, the Spear Bearer, has been considered the ideal portrayal of the human figure. This sculpture represents a canon, i.e. a kind of model for how the human body should ideally be depicted. Its author Polykleitos, who's also the creator of the statue of the victorious athlete Diadumenos, tying a diadem (ribbon-band) around his head to celebrate his victory.

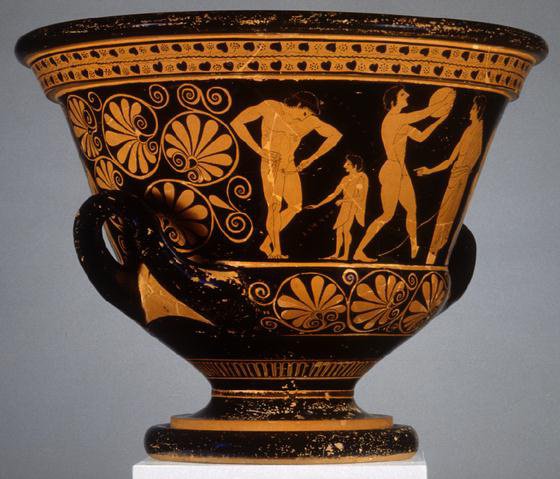

While sculptors in Ancient Greece more often portrayed individual athletes, in painting we find more complex sports scenes comprising of multiple figures. Paintings rendered on vases frequently depict events associated with athletic races. And it's not just the men right in the middle of a competition; the vessels were often decorated with images capturing moments which preceded or followed the race or scenes from the practice. Some of the paintings show that the Ancient Greeks didn't shy away from even more intimate moments. For example, the vase decoration by Euphronius, in which an athlete is captured tying a kynodesmē (a string which was supposed to prevent the glans penis from being exposed in public). Among preserved vessels is also one with two athletes depicted after the race, hugging and kissing each other.

Flesh and sin

In Western medieval philosophy, the unity of the good and the beauty completely disintegrated. Although the Christian attitude towards the flesh is full of contradictions, owing to Christian morality it was primarily associated with sin. Sexuality was strongly suppressed in medieval Christian society; it was allowed only in marriage, and on top of that exclusively for the purpose of procreation. Those with the highest ranks in this society were those abstaining from sexual activities. Western medieval art is almost exclusively related to church. Although seldom, sexuality and physicality have found their way in it, too, but rather as a portrayal of dangerous sin; such examples can be found in the Czech Republic as well. For example, on the head of the column in the Castle Chapel of St Erhard and St Ursula in Cheb, we find the depiction of lust as a mortal sin; on the Church of St. John the Baptist in Brno there's a small statue of a naked copulating human, the Indecent Little Man.

Jacques LeGoff writes: "If we do not embrace the well-established concept of salvation and the fear of hell that was omnipresent in medieval society, we will never understand their mentality..."

Although free time didn't disappear during the industrial revolution, it changed its character. In recent centuries, labor has become the end goal itself; we often derive our identity from the profession we have, whereas the ancient paradigm saw a person's identity rather from the way they spent their free time. No wonder that in modern history there are recurrent tendencies to resurrect the spirit of kalokagathia, or at least to build on it.

The most significant step in this direction of the modern era was the restoration of the Olympic Games. At the instigation of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the first modern Olympic Games were held in Athens in 1896. The restoration of the spirit of kalokagathia in Czech history is embodied by the revivalist Miroslav Tyrš. This art historian and university teacher played a role in the founding of Sokol, the first organized gymnastic movement in our country.

.jpg)